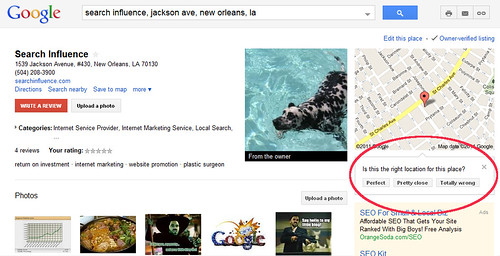

An interesting new Google Maps interface was found this past week by Daniel Hollerung, and after he tweeted Mike Blumenthal and I about it, Google Places confirmed it was an interface they are testing for verifying map accuracy. I’ve replicated an example of the interface using the listing for my friends over at Search Influence:

While this particular Google Places information accuracy widget is new, Google has long been leveraging similar user-generated content to try to enhance and grow map information. They have been actively crowd-sourcing map accuracy work for a while now, but it’s not without significant issues.

Obviously, one of the more serious issues involved is the fact that people will lie and cheat.

So, it’s no surprise that Google Maps help groups have instances reported where people suspect that their locations have been compromised some by malicious competitors, disgruntled former employees, or randomly psychotic customers. I’ve had clients and colleagues approach me with similar reports, and Mike Blumenthal has reported these types of stories as well.

Not only can some of the general public be expected to purposefully try to cause mischief, well-meaning people can also ignorantly make mistakes in commenting or reporting on data accuracy — just think of all the stories throughout popular culture of stereotyped representations of men who can’t find addresses while driving (and refuse to ask directions) or spatially-challenged women who can’t read maps. I’m not suggesting that these stereotypes are accurate representations of the sexes, but that the stories likely come from the fact that many people, regardless of sex, find navigation and map interpretation highly challenging.

So, there are some inherent problems with attempting to base a large percentage of location accuracy upon crowd sourced information.

What’s particularly concerning about Google’s methodology is that they’ve recently declared that they’ll sometimes use this data to override business owners’ disclosed information, or call into question accuracy in consumers’ minds. Blumenthal hilariously communicated the issue in his brother-in-law’s open letter response to the matter. An actively-engaged business owner may have gone in and verified that their address and map are correct in Google Places, but if a small handful of users claim the address is wrong, it can get incorrectly flagged as being a closed location, or that the address may be wrong — something which would clearly discourage potential customers from going to the business.

Mike organized a really humorous experiment to illustrate this issue when he asked a handful of us to go in and flag Google’s own corporate headquarters as “closed”. Continue reading →

I recently highlighted how social media newcomer Pinterest is good for SEO, and it’s useful for local SEO as well. Another relative newcomer worth looking to for optimizing infographics is Visual.ly.

I recently highlighted how social media newcomer Pinterest is good for SEO, and it’s useful for local SEO as well. Another relative newcomer worth looking to for optimizing infographics is Visual.ly.